|

AMEZAGA EGUBERRIAK 12-2008 ALZUZA PAMPLONA HOMENAJE A PELLO IRUJO

|

|

| . |

| Antecedentes Travesia The Lives of Vicente Amezaga y Mercedes Iribarren |

|

|

The Lives of

Mirentxu Amezaga

The Endless Journey

Mirentxu Amezaga

I met my parents at the age

of nine after a long absence of almost seven years which covered my childhood,

during which I lived surrounded by my grandparents, uncle, aunts and

occasionally my sister. During those

years I lived in Las Arenas, Getxo (Basque Country), my mother’s town. I went to the same school as she and I had

the same teacher she once had. I

performed in several roles at the children’s theater as she did during her

teenage years. Every week I visited my

paternal grandmother who lived in the nearby town of

One day I too left

everything that was so familiar to me in this tiny part of Europe to go to meet

my parents and younger siblings who had been born in

My father lived 32 years in

exile dreaming constantly of his return.

His exiled life was always marked by the pain of being so far from his

native land; and since physical return was prohibited to him he transferred

himself spiritually to his country by means of the pen. By writing he reflected his feelings about

each of the different circumstances he was living with his nostalgia, his pain,

and his love for what he had left behind.

By the spoken word he captured his audience with an energy and

conviction possible only for a soul that felt it as much as he did. And with his exceptional talent he could

express himself in an almost perfect way.

My father was a very

affectionate person. He loved his

children and he always found the time for us, guiding or teaching us in

anything we needed. He was an optimist,

a dreamer and he had a quick temper. He

was a person charged with strong emotions even though he calmed down

quickly. He was generous and

understanding to a point. He had a very

simple heart, and he loved nature and the enchantment that surrounded him in

the trees, mountains and rivers. He

loved beauty in everything. He had an

insatiable longing for culture. He was a

fervent Catholic but not to extremes. He

used examples from the Bible to teach us lessons for our daily life. He loved to have my mother and all of us

together for the main meal of the day, generally the lunch hour. That time was a special time for all of us

because he made it that way. He used to

discuss the subject of the day or the topic that bothered us at that

moment. His most outstanding virtue was

loyalty, to his family, his Church, his country and his friends.

A person from his home town

of

“In the second place he was

a devout enthusiast of linguistic studies.

Not knowing the Basque language in his youth, he became a scholar of

that language. He became a

polyglot. He mastered eight languages.

“And in the third place he

was a writer of two different currents.

On the one hand, he was a tireless investigator and analyst of historic

events which captured his interest as he was always looking for the unknown and

hidden truth. The fruit of this research

were his four published books and an immense number of articles in magazines

and newspapers. On the other hand, he

was a poet as was seen in the lyric prose of his many works and his extensive

poetic compositions.”

My mother had a completely

different character. She had the gift of

a serene and patient personality, the still water to the restless spirit of my

father. She was his loyal companion, his

help, his consolation and his strength.

They had the good luck to have each other. The constant absence of their second

daughter, Begoña, was for my parents one of the worst parts of their lives in

exile.

Born in

In war not all the wounded

are on the battlefield. There are other

wounded, those who suffer emotional wounds that last more than one

generation. This is the story of one of

them.

My father lived most of his

adult life in exile. Exile is an

invisible disadvantage. Exiles have the

same level of knowledge as other citizens, many times more, sharpened by their

intensely aggressive development, by the need to make their way, and by

adapting to the new environment that surrounds them, which makes their effort

and work doubly difficult.

One of the many

disadvantages of the exile is frustration because he/she can’t communicate in a

new world that does not understand his/her experiences. The life of the exile is one of continuous

living in an adopted environment which produces a sense of loneliness and

isolation that will remain forever. My

father talks about this in his writing “

At the same time there

exists a sense of unity, of belonging and friendship and love higher than in

the rest of the citizenry. In “Siempre

Contigo,” my father speaks of a black and bitter sea, of one long expatriation

with the searing absence of his two little daughters, but he has not become

desperate because he has his sweet wife with him. Perhaps this sense would not exist at that

level if the exile were not so vulnerable.

Sometimes exiles develop

their highest capacity because of the higher level of competition. History has given us examples of people who

have left their countries for one reason or another and who, upon arriving in

their adopted country, distinguish themselves in an absolute way. Vladimir Zworykin, born in Russia, invented

the television in the

Another problem that the

exile faces is a life of financial uncertainty.

He also suffers from an identity crisis because he/she cannot officially

count on the government of his/her country for support. My father says in his poem “Desterrado”

“Today I have no country, no land, and no rights to my native country or home.”

In the case of my father,

all these frustrations affected the rhythm of his steps and increased the value

of his life through an extensive work that he has left to us. The continual sacrifice he made in his life

would not have happened if he continued living in Algorta as the Judge of

Getxo.

The exile who has lived in

two worlds – his own and the borrowed – has experienced the double feelings of

exaltation and happiness at the same time as the frustrations of each culture

in which he has lived, and all that gives him a certain understanding lacked by

a person who has lived in only one culture, but at what a price!

The Basques

Robert Clark and Mirentxu Amezaga

As it was for most Basques, the lives of the Iribarrens and the

Amezagas were stable and relatively unchanging until the terrible decade of the

1930s. Unlike Americans, Basques know

where they have been for thousands of years.

They are truly one of the ancient and unchanged peoples of

If somehow it were possible to arrange the world so that everyone lived in ethnically homogeneous communities, each with its own political order, and without any other peoples living alongside them as minorities, the world would have been spared quite a lot of conflict and violence over the last ten millennia. (The world might also have been much less interesting and creative, as well.) But human beings have the notable tendency to want to move from where they are to someplace else, and over the course of one hundred millennia or so we have all become so mixed up and intermingled that nothing short of an act of God would be required to achieve any significant degree of homogeneity. In most instances, political boundaries do not coincide with ethnic, racial or linguistic divisions. Many leaders and many peoples have fought violently to make those lines coincide, nearly always with tragic results. Some peoples have been pursued almost to the point of extinction; the gypsies and the Maya come quickly to mind. But others have resisted assimilation and at great cost have endured and are today living in relative calm. The Basques would fall in this category even though there were moments in the last one hundred years when the outcome of that struggle was in great doubt. How they fared had much to do with the lives of the Amezagas, the Iribarrens, and their children and beyond for generations.

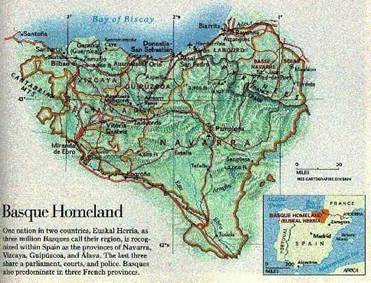

The Basque Country, known

in the Basque language as Euskadi, is on the coast of the Bay of Biscay,

primarily in two autonomous regions – The Basque Country and Navarre --, and in

the Pyrenees in southwest France, for a total of seven provinces. Euskadi is one of the most beautiful places

on earth. It is green and grassy,

crossed by a chain of mountain streams that coil through steep, narrow valleys

in their search for the sea.

Despite the decline, the

Basques survived as a nation throughout.

When they finally did agree to recognize Castilla it was on their own

terms, retaining the fueros (ancient privileges) and ancient laws, one of which was that every

king upon being crowned should come to Gernika and swear under the sacred oak

tree to uphold their laws. Since then,

Basques always played an important role in Spanish affairs, far out of

proportion to their numbers. They were

great sailors and explorers, shipbuilders and whalers, conquistadores and

pirates. They organized the first whale

fishery; in the Middle Ages Basque sailors helped the English conquer

Loyola was born at his

family’s ancestral castle in Guipuzcoa.

He was seriously wounded in 1521 at the siege of Pampeluna (now

Algorta and Las Arenas

Vicente Amezaga and Mercedes Iribarren were from the neighboring

towns of Algorta and Las Arenas. These

towns are two of the four (the others are

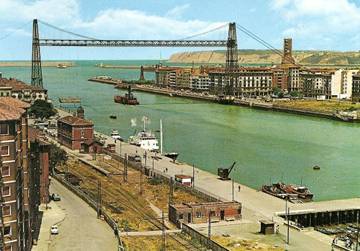

This aerial photograph, taken from a 1960s tourist guide, shows Las

Arenas and Algorta together. Las Arenas

is in the lower half of the photo, the mass of buildings on the right bank of

the river as it flows into the

The picture below, taken from a postcard, shows the town of

The two pictures below show the original old fishing

The fishing

Las Arenas is a relatively new city whose origins date back only to the middle of the nineteenth century, and for much of its history it has been relatively small, peaceful and rather out of the mainstream of Spanish and Basque history.

Until

the mid-nineteenth century, Las Arenas had only a small population because of

the sand bars that were piled up by the action of the waves coming from off the

Until

the mid-nineteenth century, Las Arenas had only a small population because of

the sand bars that were piled up by the action of the waves coming from off the

Beginning in 1880, a number of large and expensive engineering

projects were undertaken that resolved the problem of the sand deposits. These projects included a pier and eventually

a major port at Las Arenas and a breakwater that extended into the bay to

reduce the effects of the waves on the bay floor. In the preceding picture, you can see in the

distance the structures that extend out into the water to form a narrow opening

through which the vessels pass on their way between

The picture also highlights the most noteworthy engineering

structure in Las Arenas, the so-called “hanging bridge” (Puente Colgante) for which the city is famous. The “bridge” is not really a bridge at all

but a massive steel scaffolding from which is suspended a shuttle that carries

cars, trucks and people back and forth between the right bank, Las Arenas, and

the left, Portugalete. Construction of

the scaffolding began in 1890 and was completed in 1899. The scaffolding is held up by pillars or

towers that are about 150 feet high and anchored by piers sunk more than 30

feet into the sandy soil. When ships

pass under the scaffold, passage of the shuttle is halted temporarily. Despite the scaffold’s height, there have

been instances when a vessel that passed under the bridge coming into

Once the mouth of the river became passable and the two sides of the

river connected, the industrial, commercial and professional life of

At the beginning of Las

Arenas’ history as a resort, the chalets (the first was built in 1904) and

small palaces there were open only for the summer season. For the rest of the year it was a ghost town,

but soon it became filled with suburban apartments. In the next twenty years more than 120

buildings were constructed. It has a

unique attraction – the

Several

social and institutional developments were also important to the emergence of

Las Arenas as a town in its own right prior to the 1930s. Some of these, like the central market,

public schools, municipal government, health care, and sports teams were of

little importance to our story. But

several turned out to be extremely important.

In 1886, the town was granted its first Catholic parish, named Las

Mercedes, and its first large church, carrying the same name, was

constructed. The Amezagas were married

in this church in 1937 under the dramatic circumstances described below. The church was burned during the retreat of

Basque nationalists from

Several

social and institutional developments were also important to the emergence of

Las Arenas as a town in its own right prior to the 1930s. Some of these, like the central market,

public schools, municipal government, health care, and sports teams were of

little importance to our story. But

several turned out to be extremely important.

In 1886, the town was granted its first Catholic parish, named Las

Mercedes, and its first large church, carrying the same name, was

constructed. The Amezagas were married

in this church in 1937 under the dramatic circumstances described below. The church was burned during the retreat of

Basque nationalists from

The parish and the church quickly became the center of religious,

social, cultural, and community life in Las Arenas. The parish created an association called

Accion Catolica (Catholic Action) to attract the youth of the town and direct

their energies toward responsible activities.

They also created a Casa Social (

The Iribarrens

Many Basque family names are derived from a place name that has

geographic, topographic or botanical significance. The name Iribarren (also spelled Iribaren,

Yribarren, and Hiribarren) is derived from the Basque words iri (or hiri) which means “town” or “village” and barren which means the “lowest or most central part of”. Thus, translated more or less literally, the Iribarren were the “people who came from

the lowest or most central part of (the bottom of) the town (valley)”. The earliest record (mid-sixteenth century)

we have of the Iribarren family name comes from the mountainous valleys of the

Pyrenees near the border between

By the seventeenth century, when the family name begins to appear in

neighboring

The name

Gorostegui (also spelled Gorostegi), comes from the Basque words goros, meaning a species of holly tree

or bush known as European Holly, and tegi,

meaning “place”. Thus long ago their

family came from “a place where European Holly grows”. This family name comes from the town of

These photos

of Inocencio and Juliana are from an unknown date, probably taken in Las

Arenas.

These photos

of Inocencio and Juliana are from an unknown date, probably taken in Las

Arenas.

In 1895, shortly after the birth of their first child, a girl named Dolores

(called Lola), Inocencio and Juliana moved to Las Arenas, a rapidly growing

suburb of

After their move to Las Arenas, five more children were born to Inocencio and Juliana: the second died in infancy; the four surviving children were a boy, named Inocencio after his father, and three girls – Juliana (or Juli), Maria (or Mari) and the youngest, Mercedes. Mercedes was born in Las Arenas on September 10, 1905. According to the note on the back, the photo on the next page was taken in Las Arenas on the occasion of Mercedes’ seventh birthday. It depicts the five Iribarren siblings, from the left: Mari, Lola, Mercedes, Juli and Inocencio. Each is holding a symbol of their hobby. Lola, an avid reader, is holding a book; Mercedes, a bouquet of flowers; Juli, a fashion magazine; Inocencio, a tennis racket. Mari’s hobby, playing the piano, apparently did not lend itself to this representation.

My mother was born in Las

Arenas, Vizcaya, a tourist resort village established in 1868. The town featured an endless variety of

gardens and beautiful beaches, and wharves where multicolored yachts waited to

be sailed into the

My mother came from a

family of six children. (The second

child died during infancy.) My mother

was the youngest. Her mother after five

long years of suffering died of cancer when my mother was only eleven years

old, leaving her widowed father with five kids and two other children of whom

he was the foster father and several aunts who took care of the house. My grandfather was a ship’s officer but he

quit and opened a business building ships that was very successful.

My mother had just finished

school and was the administrator of her sister’s business when she met my

father. She had a lot of admirers. Her quiet, reserved and calm personality

complemented very well the intellectual, restless dreamer who was my

father. During the nine years of their

courtship they knitted a strong love that would last to the end of their lives.

In the years around the turn of the twentieth century, Talleres Erandio did reasonably well and the Iribarren family enjoyed the comfortable life style of the growing middle class of Vizcaya. Mercedes Iribarren was born in the family apartment in this elegant building, and she lived there until she married and left Las Arenas. The photo on the left is from the time when the Iribarrens lived in the apartment; that on the right is contemporary.

The Iribarren family embraced the values and programs of Basque nationalism at the time, and Inocencio was told on several occasions that he could not attend Mass wearing the Basque flag on his coat lapel. Both Inocencio and Juliana spoke Euskera as their first language, but class and social pressures of the time dictated that urban families abandon Euskera for the more popular and socially acceptable Spanish, so of the children only Lola learned to speak Euskera with fluency. In 1911, their comfortable life was shattered when Juliana was diagnosed with cancer and, after a long and painful illness, died in 1916. Mercedes was only 11 years old. Inocencio tried to fulfill the role of mother but inevitably most of those responsibilities passed to the eldest child, Lola, who was then 21.

The

five Iribarren children loved live theater and they all participated in local

Las Arenas theatre groups associated with either the Catholic parish of Las

Mercedes or with the meeting hall (called the batzoki) of the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV). The eldest, Lola, directed the productions;

Juli sewed the costumes; Mari played the piano; Inocencio handled special

effects (one of their favorites was to simulate thunder by dropping bags of

potatoes down stairs); and Mercedes, the youngest, acted. She apparently became quite a popular local

celebrity, especially with the youth of the town, for her acting ability and

delicate good looks and manner. In the

photo on the left, Mercedes appears standing on the far left as a member of a

cast presenting a play in Las Arenas. (The costumes are of traditional Basque

peasant girls.) On the right is a photo

of her school, El Colegio de la Divina Pastora, as it appeared during the first

half of the century.

The

five Iribarren children loved live theater and they all participated in local

Las Arenas theatre groups associated with either the Catholic parish of Las

Mercedes or with the meeting hall (called the batzoki) of the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV). The eldest, Lola, directed the productions;

Juli sewed the costumes; Mari played the piano; Inocencio handled special

effects (one of their favorites was to simulate thunder by dropping bags of

potatoes down stairs); and Mercedes, the youngest, acted. She apparently became quite a popular local

celebrity, especially with the youth of the town, for her acting ability and

delicate good looks and manner. In the

photo on the left, Mercedes appears standing on the far left as a member of a

cast presenting a play in Las Arenas. (The costumes are of traditional Basque

peasant girls.) On the right is a photo

of her school, El Colegio de la Divina Pastora, as it appeared during the first

half of the century.

In 1926, while acting in a play entitled “Cancion de Cuna” (“Cradle

Song”) for the local PNV meeting hall, Mercedes caught the eye of a young law

student from the neighboring town of