|

AMEZAGA EGUBERRIAK 12-2008 ALZUZA PAMPLONA HOMENAJE A PELLO IRUJO

|

|

|

|

| Antecedentes Travesia The Lives of Vicente Amezaga y Mercedes Iribarren |

|

|

Venezuela: 1955-1969

In 1955, Aita made the difficult decision to explore a job opportunity in Caracas, Venezuela. The reasons were largely economic. The family had been in difficult financial circumstances in Montevideo, where Aita supported them all with a combination of jobs, including teaching and translating. Aita was now in his mid fifties and becoming anxious about the long term prospects for himself and his family. In the mid-1950s two of Ama’s sisters (Tia Lola and Tia Mari) and a niece (Maria Louisa, daughter of Mari) were living in Caracas and they urged him to come there because the city was experiencing an economic boom and he could certainly find a better paying job. In particular, Maria Louisa’s husband was looking for someone trustworthy to be the accountant for his company, and since Aita had studied business before he went to law school and had worked as an accountant in Montevideo, they thought he would make an ideal candidate.

The plan was for Aita to go to Caracas alone and stay three months to see how he liked the job and the surroundings. Ama and the children would join him if all went well, but they all hoped that he would return to Montevideo so they could stay there.

In my last year of high school I allowed myself to be drawn more and more into the daily routine of the school and the convent. I was preparing with more joy and the years before for their annual retreat, a period of three days during which the ordinary high school schedule stopped completely to allow each of us to examine the state of our conscience and to meditate on our eternal destiny. During the retreat silence was supposed to be complete, interrupted only to go to the chapel for prayers and songs, and to hear a series of lectures by the Dominican priests. This atmosphere made me emerge from the retreat happy and more at peace with myself than I had ever been before. Now I enjoyed more of the beauty of simple things that I had taken for granted like the beauty of the sky and stars the many-colored flowers in the park, the birds singing and the trees in bloom.

For some reason the retreat molded and impressed me in some way. The silence of those days spoke to me of a different kind of happiness. Gradually I was getting detached from the activities of the outside world to concentrate on the school and the convent. I went to Mass at dawn every day, walking alone through the still, dark streets. Something brought me face to face with my inner self and inspired in me a growing commitment to the silent world of prayers, and the external things outside the walls of that building faded into the distance. My academic ambitions continued. Even though I loved biology I only won the awards for attendance and religion, evidence of a desire to be at school every day and as a result of being in good health. But now my religious horizons were expanded and I was totally involved in learning and deepening my religious faith. I was more introverted and I found pleasure in solitude in the healing silence of religious life.

I had been many times to the empty chapel by myself to pray for direction. In the background I heard the angelical voices of the nuns singing which filled the small church and I felt completely transported to another world. I started to think that I wanted to belong to this peaceful, quiet, spiritual life where there was security, compassion and understanding. At least that was how I felt. About this time a very good friend of mine suddenly left her boy friend and decided to become a nun. Carmencita (now Sister Rachel) invited me to her house to say goodbye.

I was committed to securing a religious life on the firm structure of the convent, which gave me support and which felt consoling in my prayers. I took this part of my life as solely mine, separated from my parents’ sad world of exiles that I didn’t want to participate in at that moment. I wanted to belong to my surroundings; I needed that security. I found in the peaceful routine of the convent life a way to sustain myself. I loved the beautiful environment of the gardens, the comfort of being in that chapel praying alone. And I also found strength in the convictions of the nuns. They gave me the support, kindness and direction that I needed. I turned to God for direction in my life, for consolation, and I found in this self-denying world of the convent the healing substance of religion, which went so well with my spiritual values and my personality.

Meanwhile I was an active participant in all the religious aspects of the school. I belonged to the group called “Accion Catolica” (Catholic Action), I went with the school choir to sing in nursing homes, I participated in the Eucharistic Congress that took place in Montevideo’s huge Estadio Centenario, which moved me more than anything else in those moments. I performed in the theater and attended “Cine Forum” events where we discussed films we had seen. I was also involved in sports, especially the basketball champion team. Involved in all these events I had been at some distance from my family so I knew nothing about their economic tensions. My father’s health started to fail. He had too much on his shoulders, and a lot of the tension was emotional. He had four children in Catholic schools, with a job that didn’t pay him what he deserved and a very active social life. For three months he had been at complete rest as he recovered from Meniere Syndrome, and he was forced to sell his apartment house in Algorta to pay our bills.

Now my closest friends started talking about going to college. Carmencita went to the convent. Mary was going to be an architect. She was a brilliant kid, one of the best in our class. Sara was going to study in England. Celina wanted to be a teacher. Lucia wanted to get married and have a lot of children. Marta wanted to travel around the world. I wanted to be a doctor. I was aware that my grades were not the best. But my father had always emphasized education as the key to success and he was disappointed. I was not a complete failure, but I knew I deserved better. I worked very hard and I enjoyed learning. I was curious to know everything new that fell into my hands. I would have liked to be asked to say what I knew but my teachers tried to ask what I did not know and I did not do well on tests. I couldn’t convince my parents of my seriousness to study medicine.

At that time I couldn’t understand their concerns over money until my father announced to us that he was going to Caracas to try a better job offer. We children were sad with the news. We didn’t want him away from home for three months. He had never been away for even a week. My parents were not happy with that decision either. My father explained to us that it was a tempting offer and he thought he should try it because it was getting very hard for him to maintain the same level economically for the whole family. The offer came from my cousin Maria Luisa, the daughter of my mother’s sister. Her husband, who was in a very good economic situation, needed a person whom he could trust to run his business when he was absent on his frequent business trips to Italy, and they thought of my father.

He left July 17, 1955, planning to be back to see us after school finished in December, if he decided to stay. My mother thought the deal was too good to be true and that he would return soon to stay. She wanted this badly. She was left with the four of us ranging in age from 8 to 17. I was going to graduate from high school that year. When we came back from the airport the house looked very bare and we tried to get busy to forget the empty feeling inside us.

One month after arriving in Caracas, my father

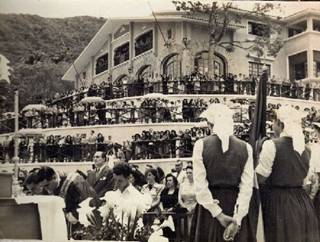

met some old friends in the Basque Center in Caracas, which had served as a

sanctuary for Basque refugees since its founding in 1942. The group offered Aita the position of secretary of the Center

and he accepted even though the job paid less and offered less security than

the accountant position. Shortly after this, President Aguirre visited Caracas and the Center (seen here speaking to a large crowd at the Basque Center). At that time, he raised with Aita the possibility that the Basque Government (now

situated in Paris) would have a job for him to establish a Basque cultural

library in France near the Spanish border. Since the Franco government was trying

ferociously to suppress the use of Euskera, this library would have the

responsibility of acquiring works in the Basque language and keeping alive the

hope of preserving the language for the next generation. Aita was overjoyed

with this opportunity: a dream job near his home.

One month after arriving in Caracas, my father

met some old friends in the Basque Center in Caracas, which had served as a

sanctuary for Basque refugees since its founding in 1942. The group offered Aita the position of secretary of the Center

and he accepted even though the job paid less and offered less security than

the accountant position. Shortly after this, President Aguirre visited Caracas and the Center (seen here speaking to a large crowd at the Basque Center). At that time, he raised with Aita the possibility that the Basque Government (now

situated in Paris) would have a job for him to establish a Basque cultural

library in France near the Spanish border. Since the Franco government was trying

ferociously to suppress the use of Euskera, this library would have the

responsibility of acquiring works in the Basque language and keeping alive the

hope of preserving the language for the next generation. Aita was overjoyed

with this opportunity: a dream job near his home.

Three months passed and my father decided to stay in Caracas even though not completely convinced about the new job. The salary he received was double what he earned in Uruguay. But he wrote us to prepare a trip to the Basque Country first and then if he was still in Caracas we would meet him there because there was other business going on. The Basque President Aguirre visited Caracas and talked about an offer to my father: a research job in Basque culture, perhaps in St. Jean-de-Luz in France. My father’s hope and joy were intense. So that was the reason why he couldn’t think of anything except to move his family to the Basque Country where he was hoping to be in a few months. Also this would give my mother a chance to meet her Begona, now 16 years old.

My mother was not happy at all about moving from that beloved country, our friends and our house, but she was eager to see her second daughter, now a young woman, and she felt my father’s happiness and followed his wishes. I wanted to live the rest of my life in Uruguay I said in anguish, stubbornness and selfishness. I loved that country and I didn’t want to cut loose from my school, friends, future plans, streets, parks, and objects of my daily life that had now grown familiar. But for my parents it was worse. They had already experienced the harrowing process of leave taking when they said goodbye to the land of their birth and such grief was enough. I didn’t enjoy hearing that comment from my mother’s friend because she should know that I had experienced leave taking too and at a very tender age. But maybe as a consequence of the change in my early years she thought it would be easier for me. My parents complained more than once about my detachment from the family more in these last years of my high school when my mother needed me the most. As a reaction I was more evasive and rebellious.

Now the next step was to sell the furniture, pictures, and so forth. We were allowed to pack in our suitcase a few items that were most dear to us as the only souvenirs from the life and land we loved so much. My mother tried several times to convince my father to come back, but it was decided. These were long months of packing, especially my father’s library which had to be packed in trunks. My mother as always in her quiet way did it all by herself and she had a gigantic job ahead of her.

I took a last look at the school where I had spent the past eight years and which had been the center of my existence. The patios looked deserted. The only sound was the lector from the nuns’ dining room reading aloud religious passages at their meal time. I waited to say goodbye to some of them sitting down on one of the benches. I looked at the two marble statues of St. Dominic with the coat of arms of the Order, and the Virgin Mary. They had been my silent friends but now I felt as if they came to life to say goodbye to me. Soon Sister Sophie and several other nuns came. Later that afternoon my school friends invited me to a coffee shop for a tea and pastries. It was an emotional afternoon. My neighborhood friends prepared a pizza party for my siblings and me at one of their houses and at the end the mother played “Adios Muchachos” (“Goodbye Boys”), a famous song of the Argentine tango singer, Carlos Gardel.

Our friends in Euskal-Erria prepared a party for all of us, especially for my mother. They spoke highly of both my parents and presented my mother with a gift. One of the elderly ladies, in the name of all those we had helped at Christmas time with baskets of food, wrote an emotional poem and gave it to my mother along with a bunch of roses. Our last week there we left the house and I stayed with the Biraben’s. They had been like a second family to me and very close friends of my parents. When the time came to say goodbye I felt a sudden feeling of intense loneliness again, cut off from every familiar object, and I felt that everything seemed cold, distant and strange.

In the early hours of Saturday, April 7, 1956, we

boarded the French vessel Provence. Our friends gathered at the harbor and with tears in our eyes we

said goodbye to all of them for the last time. Soon the Provence made its way slowly across the Atlantic.

In the early hours of Saturday, April 7, 1956, we

boarded the French vessel Provence. Our friends gathered at the harbor and with tears in our eyes we

said goodbye to all of them for the last time. Soon the Provence made its way slowly across the Atlantic.

Even though my parents tried so hard to make us Basque, the culture around us was a strong influence for us kids. Uruguay was a beautiful country and its people gave us (the entire family) all the warmth and generosity a host country can give. As a result, growing up there it was very easy for me to think, to feel and to be just like any other Uruguayan.

When we just couldn’t see any of our friends

because of the distance and because the tears blurred our eyes, we went to the

dining room and we saw other people to talk with. Soon we met other young

people and joined in the daily deck games. We stopped in different parts of Brazil. The most beautiful was the astonishing harbor of Rio de Janeiro. We went to the

top of Corcavado Mountain where there is a large status called Christ the

Redeemer from where we could see a splendid view of the city, and we wrote our

names on the stone below the statue. When we crossed the equator we had a

special celebration aboard. After Mass, there was a parade of Neptune (god of

the sea) and his retinue. A baptism ceremony was performed by him. I was

given the name “Estrella de Mar” (“Star of the Sea”). There were a lot of

games and prizes all morning, and that night after an especially good supper

there was a special gala dance. I was proud to wear a Christian Dior dress, a

gift from my godmother, Tia Juli, but my mother didn’t let me stay past 11:30,

to my disappointment.

When we just couldn’t see any of our friends

because of the distance and because the tears blurred our eyes, we went to the

dining room and we saw other people to talk with. Soon we met other young

people and joined in the daily deck games. We stopped in different parts of Brazil. The most beautiful was the astonishing harbor of Rio de Janeiro. We went to the

top of Corcavado Mountain where there is a large status called Christ the

Redeemer from where we could see a splendid view of the city, and we wrote our

names on the stone below the statue. When we crossed the equator we had a

special celebration aboard. After Mass, there was a parade of Neptune (god of

the sea) and his retinue. A baptism ceremony was performed by him. I was

given the name “Estrella de Mar” (“Star of the Sea”). There were a lot of

games and prizes all morning, and that night after an especially good supper

there was a special gala dance. I was proud to wear a Christian Dior dress, a

gift from my godmother, Tia Juli, but my mother didn’t let me stay past 11:30,

to my disappointment.

We arrived a few days later at Dakar, and we enjoyed seeing this colorful city. The night before arriving in Barcelona we had a costume dance. I was a “Sultan,” a queen of the Turkish Empire. After those fifteen days on board, which we enjoyed immensely, we decided to awake very early the next morning so we could see the breaking day from the upper deck of the vessel. We saw the rising sun come out of the ocean; it was indescribably beautiful. In a few hours we were in Barcelona.

The Provence docked in Barcelona on April 22. The reunion

between Ama and Begona was, if anything, even more emotional than Mirentxu’s

arrival in Montevideo. Ama briefly lost consciousness so intense was her

feelings. But it soon became clear to her that Begona, who was now 16 years

old, would not be joining the family either here or in Caracas. Too much time

had passed and too much emotion had been invested by all the parties in the

existing arrangement. Begona would continue to live with Tia Juli in San Sebastian until Juli’s death many years later. After the spring and summer of 1956,

the siblings would not be together as a group for more than fifty years.  This photo was taken in Algorta in the plaza

dedicated to Aita during their reunion in December 2008.

This photo was taken in Algorta in the plaza

dedicated to Aita during their reunion in December 2008.

Ama got another shock on this trip when she crossed into France to meet with President Aguirre and learned that his plans for the Basque library were postponed indefinitely because of the lack of funds.

The family now faced the prospect of eventually

leaving the Basque Country and joining Aita in Caracas. Their bridges to Uruguay had been burned, and they could not stay in the Basque Country indefinitely. So

Ama flew to Caracas to tell Aita the dual bad news – which his dreams of seeing

Begona and his homeland were not going to be realized, perhaps ever. In

October Arantxa went to Caracas by ship so she could accompany the large number

of trunks carrying the family’s possessions, especially Aita’s prized books. Mirentxu,

Bingen and Xabier stayed in San Sebastian, the boys to continue with school and

Mirentxu to look after them, to spend some time with her sister, to make some

new friends, and to study secretarial skills (typing, shorthand and English).

The family now faced the prospect of eventually

leaving the Basque Country and joining Aita in Caracas. Their bridges to Uruguay had been burned, and they could not stay in the Basque Country indefinitely. So

Ama flew to Caracas to tell Aita the dual bad news – which his dreams of seeing

Begona and his homeland were not going to be realized, perhaps ever. In

October Arantxa went to Caracas by ship so she could accompany the large number

of trunks carrying the family’s possessions, especially Aita’s prized books. Mirentxu,

Bingen and Xabier stayed in San Sebastian, the boys to continue with school and

Mirentxu to look after them, to spend some time with her sister, to make some

new friends, and to study secretarial skills (typing, shorthand and English).

From the plane I could see the magnificent mountains which frame the beaches of this tropical coast. The airport of Maiquetia is situated on the coast close to the Venezuelan port of La Guaira. My parents and sister were there to meet me; we hugged each other. They were happy to see me and we arrived shortly to our apartment.

This map of Caracas and the coast shows the airport, the town of La Guaira, and nearby the resort town of Macuto. (Note this last site; it will re-appear later in our story.) Even though the distance is short, the connecting highway has to cross a very rugged and high mountain pass, and the whole trip takes quite a long time, especially when you factor in Caracas traffic, always highly congested.

In silence we drove several miles across the

mountains by a superhighway that connects the airport to the city of Caracas. My father explained that the two sites are only six miles apart, but Caracas is built about 3,000 feet above sea level and to reach the pass over the coastal

range requires a climb of more than 3000 feet. Furthermore the slopes are so

steep that the railroad has to cover more than 20 miles. Bridges and tunnels

carry this modern highway through the mountains rather than over them. (It

took us half an hour just to get into the city itself.) Finally we arrived at Caracas at noon. It was scorching hot. The tropical climate makes it unbearable to walk

at noon on its cement pavements or to be in the few parks the city has. In the

tropics the nights always come at the same time, and the beautiful sunset is a

relief from the daily hot sun. The city is situated in a long narrow valley

between enormous mountains. Traffic is always bad. Trying to go to work in

the morning is a nightmare. You could hear the incessant sound of horns for

miles.

In silence we drove several miles across the

mountains by a superhighway that connects the airport to the city of Caracas. My father explained that the two sites are only six miles apart, but Caracas is built about 3,000 feet above sea level and to reach the pass over the coastal

range requires a climb of more than 3000 feet. Furthermore the slopes are so

steep that the railroad has to cover more than 20 miles. Bridges and tunnels

carry this modern highway through the mountains rather than over them. (It

took us half an hour just to get into the city itself.) Finally we arrived at Caracas at noon. It was scorching hot. The tropical climate makes it unbearable to walk

at noon on its cement pavements or to be in the few parks the city has. In the

tropics the nights always come at the same time, and the beautiful sunset is a

relief from the daily hot sun. The city is situated in a long narrow valley

between enormous mountains. Traffic is always bad. Trying to go to work in

the morning is a nightmare. You could hear the incessant sound of horns for

miles.

My father continued talking. He loved history, and he had learned a lot about Venezuela, perhaps because he had a feeling that he was going to live there the rest of his life.

Venezuela is a beautiful tropical country, a land where everything under the sun grows fast. Its people are as generous as the land. Their population has a high percentage of mestizos and blacks, and their hallmark is their music and dances. In the streets you can see young people with their headphones on dancing and following the rhythm of the music. This tropical city was very different from the other places where I had lived before.

It took us almost an hour to get home. The family had a nice, new, small apartment on the tenth floor of an apartment building in the eastern sector of the city. It had a view that faced the magnificent Mount Avila and the foothills of the Venezuelan Andes.

For me adjustment to life in Caracas was very difficult. I suffered another “culture shock”. I felt the distress of so many unpleasant changes again. At the very beginning I had to adjust to understand the Caribbean culture and to tropical food, the tropical climate, and the colorful Afro-Latin music so different from European styles. I knew I could never be one of them. I adopted in my vocabulary many of their words. They responded to me positively and that encouraged me to communicate with them successfully. Even though many times I confused them with my mixture of Uruguayan idioms, Hispanic ones, and ones from the Caribbean all in the same sentence. Also after two years I had become a woman with my own heart and mind. Coming to Venezuela all seemed like a dream and my awakening in a new foreign land again was doubly painful but more realistic.

By 1960, with the exception of Begona, the Amezaga

family was together again for the first time since Aita had left Montevideo in 1955. In addition to working at the Basque Center, Aita was employed half

time as a researcher at the Venezuelan National Archives. At about this time,

however, he lost both jobs, the former because the Center was facing a

difficult financial situation, and the latter because in the wake of the

revolution that restored democracy to Venezuela foreigners in government jobs

were fired to make room for Venezuelans. Aita soon got another position as a

researcher with the Fundacion John Boulton in Caracas. Although family

finances were precarious, Aita’s income could now be supplemented by the work

of some of the children, and the family made the decision to leave their

cramped apartment and to buy a condominium in a beautiful high-rise apartment,

“Residencias Country” (so-called because it overlooked the lush fairways and

greens of the golf course of the Caracas Country Club).

By 1960, with the exception of Begona, the Amezaga

family was together again for the first time since Aita had left Montevideo in 1955. In addition to working at the Basque Center, Aita was employed half

time as a researcher at the Venezuelan National Archives. At about this time,

however, he lost both jobs, the former because the Center was facing a

difficult financial situation, and the latter because in the wake of the

revolution that restored democracy to Venezuela foreigners in government jobs

were fired to make room for Venezuelans. Aita soon got another position as a

researcher with the Fundacion John Boulton in Caracas. Although family

finances were precarious, Aita’s income could now be supplemented by the work

of some of the children, and the family made the decision to leave their

cramped apartment and to buy a condominium in a beautiful high-rise apartment,

“Residencias Country” (so-called because it overlooked the lush fairways and

greens of the golf course of the Caracas Country Club).

This photo, taken at the celebration of Mirentxu’s twenty-first birthday in May 1959, shows the family singing “Happy Birthday” – “Zorionak Zuri” – to Mirentxu. On the left, Bingen is playing the txistu. Then from the left are Tia Lola, Mirentxu, Ama, Aita and Arantxa. Xabier took the picture.

Soon after her arrival in Caracas, Mirentxu became an active part of the social life of the young adult members of the Basque Center there. The young people of the Basque Center had an active social life with parties and excursions to some of the spectacular sites near Caracas. Mirentxu’s parents expected her to go to work when she got to Caracas to supplement the family’s income. In part, the training she had received in San Sebastian was supposed to prepare her for a secretary’s job in Caracas, and soon after her arrival she began to work for an engineering firm. She hated the work and did not show much enthusiasm for it, so her boss finally had to let her go. He did pay her a handsome severance package, however. Shortly after this, she read in the newspaper about the initiation of an up-to-date medical records program at the hospital at the Central University in Caracas. To prepare for the launching of this program, the Ministry of Public Health was offering a one-year program to train medical record librarians. Mirentxu saw in this a chance to be a part of an exciting new program and with the money from her severance pay she enrolled in the training course through most of 1960. Upon graduation she began to work at the university hospital, where she stayed until 1965. She was attracted to the medical profession and entertained ideas of entering the medical school as soon as she had completed the equivalency of her high school diploma in Venezuela. In the early 1960s, she returned briefly to Spain and the Basque Country to investigate the possibility of launching a medical records program in a hospital there. Failing to secure an offer, she returned to Caracas and resumed her life, now divided between her home and family, her Church, the Basque Center and the university hospital.

These photos from the early 1960s show Aita and Ama on their 25th wedding anniversary (1962), the entire family in 1963, and Ama and her daughters (1961)

My parents introduced me to both young and old people from the Basque Center. We were there every weekend. Now I was interested in forging my future. Since I had my high school diploma from Uruguay, I couldn’t go to the university in Caracas so I registered in a business school – Pitman – for an intensive course as a secretary. I got my diploma and started working as a secretary right away. Even though it helped financially I didn’t find the job challenging enough. The only incentive was the salary. A year passed. I had taking my high school equivalency course by course, year by year. While I was doing this I read about an intensive course as a Medical Records Librarian, to be given at the hospital of the Central University in Caracas, and based on the curriculum from the University of Chicago. It lasted twelve months, Monday through Saturday, from 8:00 am to 5:00 pm. I left my secretary’s job (actually, I was fired and used the severance pay to pay for my expenses and the medical records course for the next year) and I registered for the course. A year later, on December 15, 1960, I graduated and started working right away. I had the job I wanted, as a coder of medical records. It was a challenging job but I continued studying for my Venezuelan high school diploma because a career in medicine still was my goal.

In the meantime I had several relationships but nothing serious. Later on I started dating, but none of these interests lasted long because among other reasons I was not completely sure what direction my life should take. As Tolstoy said, “Each time of life has its own kind of love.” I was involved with my studies, my new challenging job, and the social life of the Basque Center. I was part of a big group of Basque youths. I had two especially close friends and every weekend we did a lot of things together. One was an engineer, just graduated from the university, and the other had also just finished her studies in psychology. Both of them, like most of the Basque Center youths, had been in Venezuela since they were babies and they had done their studies there. This fact gave me more incentive to continue with the boring task of finishing my high school courses to pursue my university degree because I felt I was very much behind everyone else. We went on excursions once a month to different parts of the city, hiking in the mountains or swimming at the beach. Many times we went out of town, usually on the first Sunday of the month. We met for Mass very early in the morning. It was difficult to be dressed for a hiking experience because then we were not allowed to wear pants to Mass, but we managed to sit in the back pews without being seen and then we departed by chartered buses, coming back that night. Other weekends we met to watch movies at the Basque Center that the youth group had rented, and later we danced on a small patio that the young people had helped build. This was our space, surrounded by big trees and a leafy garden that the Center had. Also I participated in the folkloric dances in the Basque community and in the choir. I even gave lectures. One time I talked about Basque romantic themes

I enjoyed working at my job in the hospital. The doctors invited us to watch special operations by the dome, and on occasion I was in the ooperating room besides the surgeon, but when I said these experiences Aita didn’t like very much to hear. My father disliked hospitals immensely. One day I took him to the hospital because of his intense pain in his right shoulder. He was diagnosed as having bursitis. He didn’t explain to the doctor that all afternoon the previous day he had been throwing stones at a tree full of mangos. My mother prepared delicious preserves with this fruit. In Montevideo she made preserves with oranges and tomatoes. It was like a ritual in both countries. All the members of the family helped with peeling the fruits. My father helped too, telling us stories to diminish our distaste for peeling, but if we could we tried to avoid that responsibility.

My hours outside the hospital were filled with Basque Center activities. In a profound sense I always remained the underdog. Ever since I could remember I was continually struggling to adjust to new and at times painful experiences of being apart, when I wanted so much to be a part of something. I desired so much for a peace that would fill my soul but I could achieve this only when I could feel that I belonged to some place, some thing, someone. In the meantime my silent struggle would continue. Sometimes I felt I had achieved a great deal; at other times I felt that I had achieved nothing at all.

My parents’ social life in Caracas was more limited than it had been in Montevideo. In Caracas we were all working harder. Even though my father didn’t go to as many lectures and cultural events as he did in Montevideo, when he did attend I accompanied him. I knew he liked for me to go with him. Also we felt more like foreigners in Caracas than we did in Montevideo. Venezuelan culture is Afro-Caribbean while Uruguayan culture is European. While more comfortable in the latter, we were mixtures of both without belonging to one or the other entirely.

Meanwhile I bought a car, the first and only one that our family had. My father enjoyed it the most when I took the whole family to the beach. Both my parents were great swimmers and they loved the ocean. Aita often said that the waves of the Caribbean were the same waters that kissed the coast of his home land. In the valley of Caracas it rains only from May to July but the rains are torrential. In a minute the land, highways and roads could be converted into swimming pools of cars. On one of these days I was going to work when it started to rain and my car was nearly drowned. I didn’t know what to do. I was afraid to open the door because the murky brown water would enter the car. I was lucky that some one saw my indecisiveness and came to my help. He drove me in his jeep just a few yards away. I couldn’t believe my eyes when a few seconds later I got out of the jeep and the only visible part of my car was its red top. I lost my car forever!

In those days a doctor from Madrid came to the Medical Records Department at the hospital to study our system of keeping medical records. He was interested in having such a system in his hospital and talked to me about this. I was going soon to the Basque Country so we decided to meet there. In the meantime I compiled our system in a notebook and took it to show to him. He used my information to open the first medical records program in Spain. He offered me a job there but it was in Madrid at a much lower salary than I was earning in Venezuela. From that trip I came back with the idea of not renting an apartment anymore but buying a house. Even though I didn’t say as much to my father, it was obvious that we needed to fix our roots in Venezuela and buying a house was the first step.

In the Basque Country the house is at the center of the culture. Unity is in the house. The individual belongs to a house, meaning to a lineage. The house, its inhabitants, the domestic animals and the land form a whole. The farmhouse is considered the nucleus of everything. The white stone farmhouses with their red tile roofs surrounded by the green pastures or landscape were built to last for countless generations. They were the ancestral mansion. The Basque house was built for perpetuity, a sacred link between the dead and the alive. Each Basque farmhouse has a name. Sometimes it is named for the family who lived there. My father could repeat the names of all the farmhouses around Algorta which carried our family’s name as if evoking their spirit.

About the Basque house it was said “The wind and the rain can penetrate, but not the King.” For centuries the Basque house had been an inviolable refuge. My father, more than any other member of the family, missed the feeling of owning a house.

Six months later our family moved to a beautiful condominium next to the Caracas Country Club. It was on the tenth floor and had a terrific view of the green of the golf course and of Mount Avila. My father enjoyed it the best. My sister and I gave part of our salary to help pay for this house. My father was 63 years old and still had two high-school-age children. Because he couldn’t work at his real profession, he couldn’t earn what he was capable of and so this house was a real burden for him economically. This apartment was sunny with big windows and a wide balcony where my mother had a little flower garden. She filled it with tropical plants and flowers making this part of the house a very inviting place to stay. With its marble and natural wood floors and beautiful doors, this apartment didn’t need much to give it a cozy warm feeling. It was much simpler than the house in Montevideo. Our apartment in Caracas faced south so it was sunny all day. We kept the windows open all day and night year round because of the mild climate. The apartment was furnished in a more casual and comfortable style than in Montevideo to match our changing life style there. We had a modern pine sofa in the living room; the green upholstery that my mother made matched the greenery of the plants. Both my parents loved and admired beauty in everything. Our home always looked orderly and with attention to details. Their good souls were always looking for the best in nature and in our home.

In Venezuela people dressed according to the climate which is always hot. Men wear white linen suits called “liqui-liquis,” with loose white cotton shirts. Venezuelans are very generous people just as nature has been generous with them. Because of the mild climate they can sleep outdoors with very little protection. They receive abundant nourishment from their tropical fruits such as bananas, mangoes and coconuts. These natural foods can sustain them without very much else. They also have a lot of flowers, which grow very quickly (over night).

At home Sunday was always a special day for us. Our religious life continued in Caracas with almost the same intensity as in Montevideo. Our faith and prayers were the strongest support in our nomadic lives. After Mass, if we didn’t have an outing with the Basques, we went to the swimming pool. It was almost empty at that time of day. Meanwhile my mother prepared the best menu of the week, based on baked chicken with wine sauce and “menestra,” or braised mixed vegetables, and a flan for desert. My father took advantage of the peace at home without us to listen to his favorite music. He sat on the terrace, looked at Mount Avila, and listened to “Scherezade” by the Russian compose Rimsky-Korsakov. This was almost a ritual for him. He also enjoyed the “Heroic” and the “Pastoral” by Chopin. My favorite composer was also a Russian, Tchaikovsky. I was introduced to his music when my parents took me to see the ballets “Sleeping Beauty” and “Swan Lake” in Montevideo. I was very much impressed!

At this time we acquired our first television set at Sears in Caracas. I remember how we watched the thrilling series “The Fugitive,” which was on almost every night. Ama and I went one night to the TV station because I was invited to compete in a game show but I lost in a preliminary round and never got on the air.

In the fall of 1964 I registered for the last year of high school at night after work. But few months later something happened that changed my plans.

Principal events from 1965 on:

· On July 21, 1965, Arantzazu Amezaga and Pello Irujo were married in Caracas.

· On September 15, 1965, Mirentxu Amezaga and Robert Clark were married in Caracas.

·

From December, 1967, to April, 1968, because of

Bob’s military service in Vietnam, Mirentxu and Anne Miren, lived with Ama y

Aita. These photos of Ama, Aita, Anne Miren and Xabier Irujo, the son of

Arantza and Pello Irujo, are among the last of both with their first

grandchildren, and the only ones Aita met.

From December, 1967, to April, 1968, because of

Bob’s military service in Vietnam, Mirentxu and Anne Miren, lived with Ama y

Aita. These photos of Ama, Aita, Anne Miren and Xabier Irujo, the son of

Arantza and Pello Irujo, are among the last of both with their first

grandchildren, and the only ones Aita met.

· On February 4, 1969, Aita passed away in Caracas, where he is buried.

· Begona, Bingen and Xabier were married after Aita’s death.

· From August 1969 until her death (1980) Ama divided her time between Caracas, Euskadi and Washington D.C. She left 16 grandchildren.

· On June 7, 1980, Ama passed away in Andorra. She was on a pilgrimage to Lourdes at the time. Her body is buried in Algorta.

· We, their, children continue to live on three continents. Bingen and Xabier in Caracas, Venezuela; Arantza in Alzuza, Navarra; Begona in San Sebastian, Guipuzcoa; and I in Burke, Virginia, USA. In 1995, I finally graduated from college, With Honors from George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia.